I’ve taken up knitting again.

I’ve been a knitter, on and off, since my mom taught me in high school. I knit my way through calculus, completing my project (a pair of socks?) but earning a horrific score on my AP test. I put my knitting away for a few years, then picked it up again as I worked through a season of clinical anxiety in my twenties, decoding my twisted emotions as I steadily added stitches to blankets, scarves, hats, gloves, and sweaters. As I healed, I kept knitting, and would often knit while watching a movie, pleased that my skill allowed me to knit by feel, rarely requiring me to look at my hands. The soothing repetition of knit and purl were ready when I needed their help to overcome a miscarriage (and another, and another), and then to dispel the anxiety that hung over my pregnancy with Lucy. (She had a lot of hand-knit hats to wear when she was born.) Over the past few years, the pressing needs of laundry-folding or light mending have absorbed my idle hands during our family movie nights, and my bamboo needles rested in a box, waiting for me to call on them again.

But about a month ago, my father-in-law fell ill and entered hospice care, where he lived out his final days. And since those days in the hospital began, I’ve been knitting — a seed-stitch scarf, using a variegated pink yarn that I picked up a year or two ago in a moment of inspiration.

The practice of knitting brings a lot of magic — the pursuit of a goal in the middle of stillness, a meditative repetition to absorb fidgety energy, a visual mystery of loop and connections that one can hardly make sense of. Knitting creates the perfect vessel to receive emotion and complexity, all while allowing the knitter to sit quietly, a non-anxious presence in the midst of human vulnerability.

Bill entered the hospital on December 26, admitted with a high fever and poor blood oxygenation. In these first days of his illness, I was not knitting. Conscious of his struggle to manage distress, we held his hands and spoke to him, reading books aloud and talking with doctors and telling stories. Once it became clear that his 88-year-old body was no match for this particular infection, the hospice team received him into their care, medicating him into a peaceful state. In this period of quiet waiting, the knitting began as we watched and witnessed.

“You can see he isn’t in pain,” the doctor would tell us. “His brow isn’t furrowed, his shoulders are relaxed, and his hands aren’t clenched.” We were grateful that Bill did seem to be resting comfortably, and we sat together, watching his quick, shallow breathing and studying his face, conscious that it would perhaps be the last time we would see it. Knit, purl, knit, purl went my seed-stitch scarf, lengthening daily.

The hospice team offered the services of a music therapist, a petite, dark-haired woman with bold glasses and a harp almost bigger than she was. Margaret joined us one afternoon and explained that she would play music in rhythm with his breathing, giving us all an opportunity to sync up with him. “Lots of people say it’s like a musical massage,” she smiled. The sounds of the harp and her voice filled the tiny room, creating space for reflection that, at times, almost felt like too much — and so into the scarf it went. Knit, purl, knit, purl.

On the few times I visited on my own, I talked with Bill a little bit, reassuring him of our love, thanking him for all the ways he planned for this moment, and even sharing a few little tidbits from the day. I read to him, and Jon read to him — Christmas stories, mostly, from a collection Jon had picked up this year, edited by an author he works with. Louisa May Alcott, Arthur Conan Doyle, Charles Dickens, Lucy Maude Montgomery. The stories did us good, and I think Bill appreciated them too, his storytelling nature affirmed through these little tales. But usually, a few of us visited together at a time, and I would knit, purl, knit, purl, the scarf receiving all the love and grief and stories and questions that infused these times.

Bill died on Saturday night, January 4 — late in the evening, around 11:30 pm. We had been with him earlier in the day and wondered if it would be the last time, and it was.

The following days were full — of emotions, of tasks, of decisions, of memories. We contacted friends and far off family, planned a memorial event, and shared stories. Everyday tasks had to be done at least a little bit — dishes, cooking, working, laundry. The outcome of this hospice experience wasn’t a surprise, but still we were shaken. I find that an encounter with death, even when expected, feels like a rip in the space-time continuum, a black hole that tosses me off balance and demands a re-orientation before I feel steady again.

The experience throws me back to those days shortly before my tenth birthday when my own father died suddenly. I recall sitting in the hospital waiting room, hearing the doctor breaking the news to my mother (“Mrs. Gortner, I’m so sorry, but your husband has died”) — and an image instantly came to my mind of me, floating in space, completely unmoored from gravity and utterly alone. This sensation has returned throughout my life, hovering nearby anytime I’m in the presence of death, echoing for the weeks and months afterward. How much of this can be attributed to my childhood trauma, and how much is just everyday, existential angst? In adulthood, I feel more intellectually comfortable with the unknowableness of the afterlife and can find the hope and warmth of those questions — and yet that black hole of fear and loss is not easily vanquished when it pops up in the dead of night. Knitting helps even with this, grounding me in the reality of the living world, connecting me with honest textures and colors and a quiet clickety-clack — knit, purl, knit, purl.

Knitting at Bill’s memorial event.

And so time marches along. On January 18, we remembered Bill’s life through a celebratory open house, instructing guests to wear bright colors to honor Bill’s adventurous spirit and to bring a written memory of him. Through those two hours, we hugged and cried and laughed, listening to story after story of the way Bill loved and welcomed those near and far. Those stories, too, were knitted into that pink scarf — knit, purl, knit, purl. The following morning, I finished off the ends, wrapped the scarf in a white ribbon, and gave it to Bill’s wife Betty.

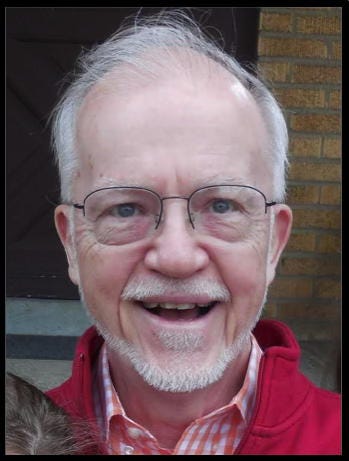

Bill Boyd was born on May 28, 1936. He was 88 years old when he died on January 4, 2025, having suffered from dementia for several years and a terminal infection for about ten days. Even in his final conscious days, he recognized us and smiled at us, reflecting back the love we feel for our family. He lived a good life, and he is already missed.

Tidbits

For this segment, I can’t think of anything better than to share the memory I wrote and read at Bill’s memorial open house.

for Bill

When I think of my father-in-law, Bill Boyd, I have a clear image of him, one that was repeated over many, many years. Whenever I came over for a visit, I would walk into their home and he would rise from his seat to greet me warmly. His whole face would light up — a big grin, bright blue eyes, arms open for a hug. We would often share a little joke and he would clap his hands or slap his legs with delight. Later in the visit, he would put an arm around me and say how happy he was to have me in the family.

The repetition of this kind of greeting never failed to give me a sense of warmth, of belonging, and of family. Having lost my own father before age 10, it always felt especially meaningful to experience such love from Bill.

Even in his last months, when words did not come easily to him, Bill never lost his bright-eyed recognition of me. After more than twenty years of welcoming me into his family, I knew he was saying it just with a smile and a hug.

We’ve been missing different parts of Bill for a few years now — the words and the questions and the never-ending plans for social engagements and trips. But I’m so grateful that, even to the very end, Bill was able to communicate his warmth and his spirit of welcome.

In Bill’s finals days, it occurred to me that he was preparing to do something that was very natural for him. In his time of leading trips with Boyd Travelers, he would routinely take a research trip, traveling ahead of the group, double-checking all arrangements and familiarizing himself with the destination so that he could welcome others when they arrived at the airport. Bill has left us now and I like to think that he is off on the ultimate research trip, preparing for the time when the rest of us will meet him. I feel certain he will welcome us with that big grin, those bright blue eyes, and a warm embrace.

Ann Boyd

January 18, 2025

Bill was a very accomplished model railroader. Jon shot this video in February 2008, a short documentary of the “Festival of Steam” Bill held for his model railroading buddies. When Lucy was two years old, this was her favorite video!

Thank you.

What a beautiful acocunt of the last days of a beautiful life. You have me in tears, in such a good way. Thank you for sharing this! (And that pink wool is so very lovely).